Hallucination

| Hallucination | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

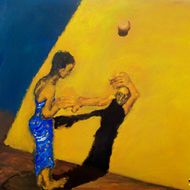

The real shadow of the hallucinating person transforms into the corporeal image. |

|

| ICD-10 | R44. |

| ICD-9 | 780.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 19769 |

| MeSH | D006212 |

A hallucination, in the broadest sense of the word, is a perception in the absence of a stimulus. In a stricter sense, hallucinations are defined as perceptions in a conscious and awake state in the absence of external stimuli which have qualities of real perception, in that they are vivid, substantial, and located in external objective space. The latter definition distinguishes hallucinations from the related phenomena of dreaming, which does not involve wakefulness; illusion, which involves distorted or misinterpreted real perception; imagery, which does not mimic real perception and is under voluntary control; and pseudohallucination, which does not mimic real perception, but is not under voluntary control.[1] Hallucinations also differ from "delusional perceptions", in which a correctly sensed and interpreted genuine perception is given some additional (and typically bizarre) significance.

Hallucinations can occur in any sensory modality — visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, proprioceptive, equilibrioceptive, nociceptive, thermoceptive and chronoceptive.

A mild form of hallucination is known as a disturbance, and can occur in any of the senses above. These may be things like seeing movement in peripheral vision, or hearing faint noises and/or voices. Auditory hallucinations are very common in schizophrenia of the paranoid type. They may be benevolent (telling the patient good things about themselves) or malicious, cursing the patient etc. Auditory hallucinations of the malicious type are frequently heard like people talking about the patient behind their back. Like auditory hallucinations, the source of their visual counterpart can also be behind the patient's back. Their visual counterpart is the feeling of being looked-stared at, usually with malicious intent. Not infrequently, auditory hallucinations and their visual counterpart are experienced by the patient together.

Hypnagogic hallucinations and hypnopompic hallucinations are considered normal phenomena. Hypnagogic hallucinations can occur as one is falling asleep and hypnopompic hallucinations occur when one is waking up.

Hallucinations can also be associated with drug use (particularly deliriants), sleep deprivation, psychosis, neurological disorders, and delirium tremens.

Contents |

Classification

Hallucinations may be manifested in a variety of forms.[2] Various forms of hallucinations affect different senses, sometimes occurring simultaneously, creating multiple sensory hallucinations for those experiencing them.

Visual

The most common modality referred to when people speak of hallucinations. These include the phenomena of seeing things which are not present or visual perception which does not reconcile with the consensus reality. There are many different causes, which have been classed as psychophysiologic (a disturbance of brain structure), psychobiochemical (a disturbance of neurotransmitters), and psychological (e.g. meaningful experiences intruding into consciousness). Numerous disorders can involve visual hallucinations, ranging from psychotic disorders to dementia to migraine, but experiencing visual hallucinations does not in itself mean there is necessarily a disorder.[3]

Auditory

Auditory hallucinations (also known as Paracusia),[4] particularly of one or more talking voices, are particularly associated with psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia or mania, and hold special significance in diagnosing these conditions, although many people not suffering from diagnosable mental illness may sometimes hear voices as well. Auditory hallucinations of non-organic origin are most often met with in paranoid schizophrenia. their visual counterpart in that disease is the non-reality-based feeling of being looked or stared at.

Other types of auditory hallucination include exploding head syndrome and musical ear syndrome, and may occur during sleep paralysis. In the latter, people will hear music playing in their mind, usually songs they are familiar with. Recent reports have also mentioned that it is also possible to get musical hallucinations from listening to music for long periods of time.[5] This can be caused by: lesions on the brain stem (often resulting from a stroke); also, tumors, encephalitis, or abscesses.[6] Other reasons include hearing loss and epileptic activity.[7] Auditory hallucinations are also a result of attempting wake-initiation of lucid dreams.

Olfactory

Phantosmia is the phenomenon of smelling odors that aren't really present. The most common odors are unpleasant smells such as rotting flesh, vomit, urine, feces, smoke, or others. Phantosmia often results from damage to the nervous tissue in the olfactory system. The damage can be caused by viral infection, brain tumor, trauma, surgery, and possibly exposure to toxins or drugs.[8] Phantosmia can also be induced by epilepsy affecting the olfactory cortex and is also thought to possibly have psychiatric origins. Phantosmia is different from parosmia, in which a smell is actually present, but perceived differently from its usual smell.

Olfactory hallucinations have also been reported in migraine, although the frequency of such hallucinations is unclear.[9][10]

Tactile

Other types of hallucinations create the sensation of tactile sensory input, simulating various types of pressure to the skin or other organs. This type of hallucination is often associated with substance use, such as someone who feels bugs crawling on them (known as formication) after a prolonged period of cocaine or amphetamine use.[11]

Stages of a hallucination

- Emergence of surprising or warded-off memory or fantasy images [12]

- Frequent reality checks [12]

- Last vestige of insight as hallucinations become "real" [12]

- Fantasy and distortion elaborated upon and confused with actual perception [12]

- Internal-external boundaries destroyed and possible pantheistic experience [12]

Cause

Hallucinations can be caused by a number of factors.

Hypnagogic hallucination

These hallucinations occur just before falling asleep, and affect a surprisingly high proportion of the population. The hallucinations can last from seconds to minutes, all the while the subject usually remains aware of the true nature of the images. These may be associated with narcolepsy. Hypnagogic hallucinations are sometimes associated with brainstem abnormalities, but this is rare.[13]

Peduncular hallucinosis

Peduncular means pertaining to the peduncle, which is a neural tract running to and from the pons on the brain stem. These hallucinations usually occur in the evenings, but not during drowsiness, as in the case of hypnagogic hallucination. The subject is usually fully conscious and then can interact with the hallucinatory characters for extended periods of time. As in the case of hypnagogic hallucinations, insight into the nature of the images remains intact. The false images can occur in any part of the visual field, and are rarely polymodal.[13]

Delirium tremens

One of the more enigmatic forms of visual hallucination is the highly variable, possibly polymodal delirium tremens. Individuals suffering from delirium tremens may be agitated and confused, especially in the later stages of this disease. Insight is gradually reduced with the progression of this disorder. Sleep is disturbed and occurs for a shorter period of time, with Rapid eye movement sleep.

Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia

Parkinson's disease is linked with Lewy body dementia for their similar hallucinatory symptoms. The symptoms strike during the evening in any part of the visual field, and are rarely polymodal. The segue into hallucination may begin with illusions[14] where sensory perception is greatly distorted, but no novel sensory information is present. These typically last for several minutes, during which time the subject may be either conscious and normal or drowsy/inaccessible. Insight into these hallucinations is usually preserved and REM sleep is usually reduced. Parkinson's disease is usually associated with a degraded substantia nigra pars compacta, but recent evidence suggests that PD affects a number of sites in the brain. Some places of noted degradation include the median raphe nuclei, the noradrenergic parts of the locus coeruleus, and the cholinergic neurons in the parabrachial and pedunculopontine nuclei of the tegmentum.[13]

Migraine coma

This type of hallucination is usually experienced during the recovery from a comatose state. The migraine coma can last for up to two days, and a state of depression is sometimes comorbid. The hallucinations occur during states of full consciousness, and insight into the hallucinatory nature of the images is preserved. It has been noted that ataxic lesions accompany the migraine coma.[13]

Charles Bonnet syndrome

Charles Bonnet syndrome is the name given to visual hallucinations experienced by blind patients. The hallucinations can usually be dispersed by opening or closing the eyelids until the visual images disappear. The hallucinations usually occur during the morning or evening, but are not dependent on low light conditions. These prolonged hallucinations usually do not disturb the patients very much, as they are aware that they are hallucinating.[13] A differential diagnosis are opthalmopathic hallucinations [15].

Focal epilepsy

The visual hallucinations from focal epilepsy are characterized by being brief and stereotyped. They are usually localized to one part of the visual field, and last only a few seconds. Other epileptic features may present themselves between visual episodes. Consciousness is usually impaired in some way, but nevertheless, insight into the hallucination is preserved. Usually, this type of focal epilepsy is caused by a lesion in the posterior temporoparietal.[13]

Schizophrenic hallucination

Hallucinations caused by schizophrenia.

Drug-induced hallucination

Hallucinations caused by the consumption of psychoactive substances.

Pathophysiology

Various theories have been put forward to explain the occurrence of hallucinations. When psychodynamic (Freudian) theories were popular in psychiatry, hallucinations were seen as a projection of unconscious wishes, thoughts and wants. As biological theories have become orthodox, hallucinations are more often thought of (by psychologists at least) as being caused by functional deficits in the brain. With reference to mental illness, the function (or dysfunction) of the neurotransmitters glutamate and dopamine are thought to be particularly important.[16] The Freudian interpretation may have an aspect of truth, as the biological hypothesis explains the physical interactions in the brain, while the Freudian deals with the origin of the flavor of the hallucination. Psychological research has argued that hallucinations may result from biases in what are known as metacognitive abilities.[17]

These are abilities that allow us to monitor or draw inferences from our own internal psychological states (such as intentions, memories, beliefs and thoughts). The ability to discriminate between internal (self-generated) and external (stimuli) sources of information is considered to be an important metacognitive skill, but one which may break down to cause hallucinatory experiences. Projection of an internal state (or a person's own reaction to another's) may arise in the form of hallucinations, especially auditory hallucinations. A recent hypothesis that is gaining acceptance concerns the role of overactive top-down processing, or strong perceptual expectations, that can generate spontaneous perceptual output (that is, hallucination).[18]

Treatments

There are few treatments for many types of hallucinations. However, for those hallucinations caused by mental disease, a psychologist or psychiatrist should be alerted, and treatment will be based on the observations of those doctors. Antipsychotic and atypical antipsychotic medication may also be utilized to treat the illness if the symptoms are severe and cause significant distress.[19] For other causes of hallucinations there is no factual evidence to support any one treatment is scientifically tested and proven. However, abstaining from hallucinogenic drugs, managing stress levels, living healthily, and getting plenty of sleep can help reduce the prevalence of hallucinations. In all cases of hallucinations, medical attention should be sought out and informed of one's specific symptoms.

Epidemiology

One study from as early as 1895[20] reported that approximately 10% of the population experienced hallucinations. A 1996-1999 survey of over 13,000 people[21] reported a much higher figure, with almost 39% of people reporting hallucinatory experiences, 27% of which were daytime hallucinations, mostly outside the context of illness or drug use. From this survey, olfactory (smell) and gustatory (taste) hallucinations seem the most common in the general population.

See also

|

|

|

Further reading

- Johnson FH (1978). The anatomy of hallucinations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall Co. ISBN 0-88229-155-6.

- Bentall RP, Slade PD (1988). Sensory deception: a scientific analysis of hallucination. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7099-3961-2.

- Aleman A, Larøi F (2008). Hallucinations: The Science of Idiosyncratic Perception. American Psychological Association (APA). ISBN 1-4338-0311-9.

Notes

- ↑ Leo P. W. Chiu (1989). "Differential diagnosis and management of hallucinations" (PDF). Journal of the Hong Kong Medical Association 41 (3): 292–7. http://sunzi1.lib.hku.hk/hkjo/view/21/2100448.pdf.

- ↑ Chen E. and Berrios G.E. (1996) Recognition of hallucinations: a multidimensional model and methodology. Psychopathology 29: 54-63.

- ↑ Visual Hallucinations: Differential Diagnosis and Treatment (2009)

- ↑ "Medical dictionary". http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/paracusia.

- ↑ Young, Ken (July 27, 2005). "IPod hallucinations face acid test". Vnunet.com. http://www.vnunet.com/vnunet/news/2140422/ipod-help-produce-musical. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ "Rare Hallucinations Make Music In The Mind". ScienceDaily.com. August 9, 2000. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2000/08/000809065249.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ Engmann, Birk; Reuter, Mike: Spontaneous perception of melodies – hallucination or epilepsy? Nervenheilkunde 2009 Apr 28: 217-221. ISSN 0722-1541

- ↑ Phantom smells

- ↑ Wolberg FL, Zeigler DK (1982). "Olfactory Hallucination in Migraine". Archives of Neurology 39 (6): 382.

- ↑ Sacks, Oliver (1986). Migraine. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 9780520058897.

- ↑ Berrios G E (1982) Tactile Hallucinations. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 45: 285-293

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Horowitz MJ (1975). "Hallucinations: An Information Processing Approach". In West LJ, Siegel RK. Hallucinations; behavior, experience, and theory. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-79096-6.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Manford M, Andermann F (Oct 1998). "Complex visual hallucinations. Clinical and neurobiological insights". Brain 121 ((Pt 10)): 1819–40. doi:10.1093/brain/121.10.1819. PMID 9798740. http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/121/10/1819.

- ↑ Mark Derr (2006) Marilyn and Me, "The New York Times" February 14, 2006

- ↑ Engmann, Birk (2008). "Phosphenes and photopsias - ischaemic origin or sensorial deprivation? - Case history" (in German). Z Neuropsychol. 19 (1): 7–13. doi:10.1024/1016-264X.19.1.7. http://www.psycontent.com/content/m507n73711u73652/?p=400b10f998844a6abe524fcf44626323&pi=1.

- ↑ Kapur S (Jan 2003). "Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia". Am J Psychiatry 160 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13. PMID 12505794. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12505794.

- ↑ Bentall RP (Jan 1990). "The illusion of reality: a review and integration of psychological research on hallucinations". Psychol Bull 107 (1): 82–95. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.82. PMID 2404293. http://content.apa.org/journals/bul/107/1/82.

- ↑ Grossberg S (Jul 2000). "How hallucinations may arise from brain mechanisms of learning, attention, and volition". J Int Neuropsychol Soc 6 (5): 583–92. doi:10.1017/S135561770065508X. PMID 10932478.

- ↑ "Hallucinations: Treatment: Information from Answers.com." Answers.com: Wiki Q&A combined with free online dictionary, thesaurus, and encyclopedias. http://www.answers.com/topic/hallucinations-treatment (accessed January 20, 2010).

- ↑ Francis Nagaraya, Myers FWH et al. (1894). "Report on the census of hallucinations". Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 34: 25–394.

- ↑ Ohayon MM (Dec 2000). "Prevalence of hallucinations and their pathological associations in the general population". Psychiatry Res 97 (2-3): 153–64. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00227-4. PMID 11166087. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165178100002274.

External links

- INTERVOICE Online, website of the international hearing voices movement

- Hearing Voices Network

- "Anthropology and Hallucinations", chapter from The Making of Religion

- "The voice inside: A practical guide to coping with hearing voices"

- Psychology Terms

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||